In a quest to make the simple PowerPoint more effective, researchers have found that the proper incorporation of

simple user interaction (in this case control over the pace of the multimedia

explanation) in a multimedia explanation (technical term for a PowerPoint that

attempts to explain a cause and effect system), can strengthen their conceptual

understanding and help them learn more deeply by decreasing the cognitive load the user experiences, a finding which is in agreement with cognitive load theory.

In a quest to make the simple PowerPoint more effective, researchers have found that the proper incorporation of

simple user interaction (in this case control over the pace of the multimedia

explanation) in a multimedia explanation (technical term for a PowerPoint that

attempts to explain a cause and effect system), can strengthen their conceptual

understanding and help them learn more deeply by decreasing the cognitive load the user experiences, a finding which is in agreement with cognitive load theory. Since cognitive load refers to the amount of information that a person's working memory can hold at one time, decreasing it decreases the amount of stress placed on the brain and helps the user learn.

Proper incorporation of user interactivity is required to effectively decrease the load though, and according to this this study the Part-Whole presentation was found to be the proper method.

The Part-Whole presentation method follows the principles of progressive method building and allows learners to first build component models that represent how every individual part of the system works, and then integrate these component models into a casual model that puts every part together into a coherent cause-and-effect chain.

This research is being done to solve the long enduring problem of being bombarded with too much information all at once and comprehending very little

Why is this important? Because every student is familiar with the PowerPoint's information chocked slides supplemented by pictures, diagrams, and whatever else your professor deems of enough importance to be featured on the big screen of his classroom.

Every student is also familiar with the vicious cycle of racing against time to mindlessly copy down (or type up) all the information before the next slide is pulled up and another concept, another chunk of information, is thrown at them, repeating this process till the end of class rolls around and they walk out with structure-less notes and a partial, vague understanding of the content they just “learned.”

In an attempt to solve this problem ,the goal of this research was to explore the possible effects of incorporating simple user interactivity on “cognitive processing during learning and the cognitive outcome of learning.” The researchers began with the hypothesis that simple user interaction would lessen the cognitive load on the user’s working memory and thus, allow them to build a more comprehensive mental model of the system and learn concepts more deeply.

The study used two groups and exposed them to four different treatments to find the best method of integrating interaction in multimedia presentations

The study consisted of two experiments in which 60 learners

were split into four groups and exposed to two 140-second, 16 part multimedia

explanations on lightning formation. There were two types of presentations in

this study – whole, which is a continuous animated narration that plays the

entire presentation with no user input, and part, which is when the material is

presented part by part and transition between parts is under the user’s control.

Researchers proposed that part presentations would give learners more time and opportunity to fully process and relate pieces of information, as opposed to an equivalent whole presentation that only allows for a specific amount of time on each slide.

Researchers proposed that part presentations would give learners more time and opportunity to fully process and relate pieces of information, as opposed to an equivalent whole presentation that only allows for a specific amount of time on each slide.

In experiment one, learners either received a whole

presentation followed by a part presentation (Whole-Part), or a part

presentation followed by a whole presentation (Part-Whole).

In experiment one, learners either received a whole

presentation followed by a part presentation (Whole-Part), or a part

presentation followed by a whole presentation (Part-Whole). In experiment two learners received either a whole presentation followed by another whole presentation (Whole-Whole), or a part presentation followed by another part presentation (Part-Part). Learners in both experiments were asked to take a cognitive load rating test after each individual presentation and then take a retention test and a transfer after viewing both presentations.

The study's results showed that the Part-Whole presentation method leads to the least amount of cognitive load on the user

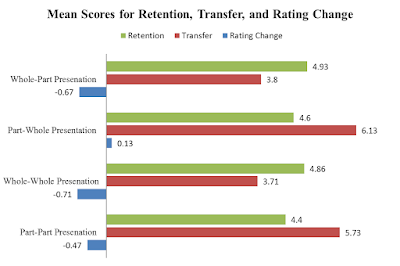

The results of the study showed that the Part-Whole and

the Part-Part groups had higher mean transfer test scores than the Whole-Part and

the Whole-Whole groups, proving that allowing learners to control the speed of

the information and move from slide to slide at their own pace helps them learn

information so that they can effectively apply it.

The results of the study showed that the Part-Whole and

the Part-Part groups had higher mean transfer test scores than the Whole-Part and

the Whole-Whole groups, proving that allowing learners to control the speed of

the information and move from slide to slide at their own pace helps them learn

information so that they can effectively apply it. The increase in mean rating score in the Part-Whole group and the decrease in the Whole-Part group supports the conclusion that learners perceived a decrease in cognitive load when shown a part presentation.

It should be noted that the retention tests across all four groups

were similar which indicates that both types of presentations were equally

effective in helping students recall the major ideas and concepts of the

topic.

These results have to be effectively applied in classroom settings by professors so that learners can glean the most information possible from presentations

These results reflect what every student who has left blank spaces in their notes during lecture has said - "if only I could slow things down and look and that slide longer." Students find it easier when they can review material at their own pace, which means that the incorporation of interactivity in presentations can definitely help learning.

But, simply incorporating interactivity will not improve learning. It is when interactivity is incorporated so that cognitive load is decreased and the two state construction of a casual model is allowed to take place that understanding can be impacted in a positive manner.

This research calls for educators to divert from the conventional method of Whole-Part presentations and to give students control of the pace during the first viewing so that they can learn in the best way possible. But, putting this into practice brings the problems of students assuming that they have all the information necessary in the PowerPoint so not coming to class, or students moving too fast through the PowerPoint.

Educators need to find a way to reconcile these pros and cons and try to develop a plan that can allow them to implement the results of research without adverse affects so that students can have the most effective learning experience possible.

These results have to be effectively applied in classroom settings by professors so that learners can glean the most information possible from presentations

These results reflect what every student who has left blank spaces in their notes during lecture has said - "if only I could slow things down and look and that slide longer." Students find it easier when they can review material at their own pace, which means that the incorporation of interactivity in presentations can definitely help learning.

But, simply incorporating interactivity will not improve learning. It is when interactivity is incorporated so that cognitive load is decreased and the two state construction of a casual model is allowed to take place that understanding can be impacted in a positive manner.

This research calls for educators to divert from the conventional method of Whole-Part presentations and to give students control of the pace during the first viewing so that they can learn in the best way possible. But, putting this into practice brings the problems of students assuming that they have all the information necessary in the PowerPoint so not coming to class, or students moving too fast through the PowerPoint.

Educators need to find a way to reconcile these pros and cons and try to develop a plan that can allow them to implement the results of research without adverse affects so that students can have the most effective learning experience possible.

I enjoyed reading Disha's article. It cogently explains the importance of including computer-user interactivity in multimedia presentations. The topic is fascinating, and the author presents it in an enthusiastic tone that engages the reader. As an example, Disha made the topic more relatable to the article's intended audience by describing the experiences of students who are hindered by PowerPoint.

ReplyDeleteIn science writing, it can be difficult to summarize the results of a study without relying on academic jargon. I felt the author succeeded in writing an article that a layperson can understand. However, there were a few technical terms and concepts that were not explained clearly. For instance, the term "cognitive load" is used repeatedly in the article, but the phrase is meaningless for someone unfamiliar with psychology.

The structure and formatting of the article made it very readable. The paragraphs were kept short enough so that the reader doesn't lose interest. The headline was explanatory rather than descriptive. I was able to understand the main point of the article just by reading the headline. The link in the article is embedded correctly. My only complaint is that the conclusion of the study isn't mentioned until the third paragraph. The author should have front-loaded their article by including the gist of the study at the beginning of the article.

The graphics used in the article effectively communicated data that is relevant to the topic. There is contiguity between the data graphics and the accompanying text. However, I did find a few flaws. One of the purposes of using a graphic is to grab the reader's attention, so at least one of the graphics should have been included besides the first two paragraphs. The chart displaying the process of the experiment lacks a title. The bar chart is missing values besides the bars, which would have made the chart easier to comprehend.

Additionally, I felt that the article could have benefited from more proofreading. I noticed several spelling and grammatical errors. For example, "from" is misspelled as "form" in paragraph seven and "equally effect" should be changed to "equally effective" in paragraph nine.

Overall, I commend the author for writing a detailed article on a difficult subject. Disha successfully incorporated the concepts we learned in class into an informative and interesting article.